CAPTAIN ST. PETER

From “Des Islas” to Stonington

The Story of Manuel Madeira and his wife Connie

From “Des Islas” to Stonington

The Story of Manuel Madeira and his wife Connie

THIS IS A STORY OF YOUNG LOVE AND MARRIAGE; BABIES AND BILLS; HEARTBREAK AND HAPPINESS; THE STORY OF A FISHERMAN’S INCREDIBLE COURAGE IN TIMES OF DISASTER.

In Vila Franca do Campo on the Island of San Miguel in the Azores, in the year 1902, a young man named Manuel Madeira, a fisherman’s son, was dreaming of going to America. His older sister Stella had gone the year before, she was living in Stonington, Connecticut with her Aunt Gloria, and had married Marion Pont. Manuel was in love with Connie Costa, then fifteen years old. Her father was also a fisherman. Manuel and Connie and her parents made the dream come true.

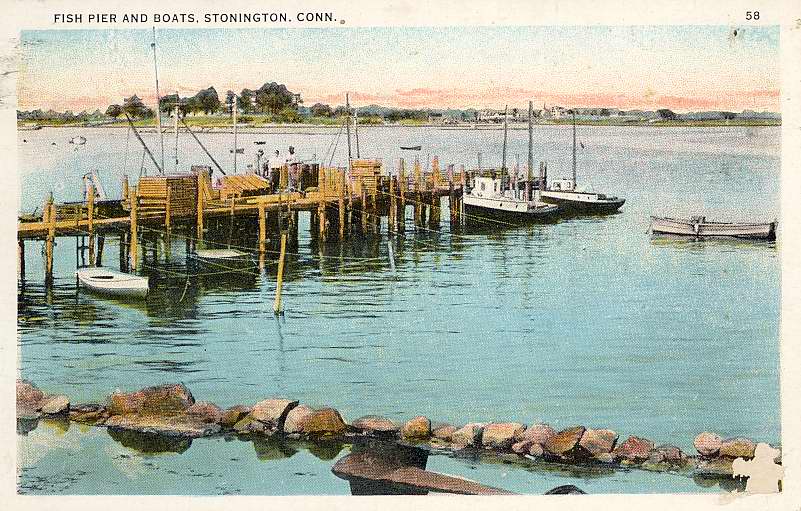

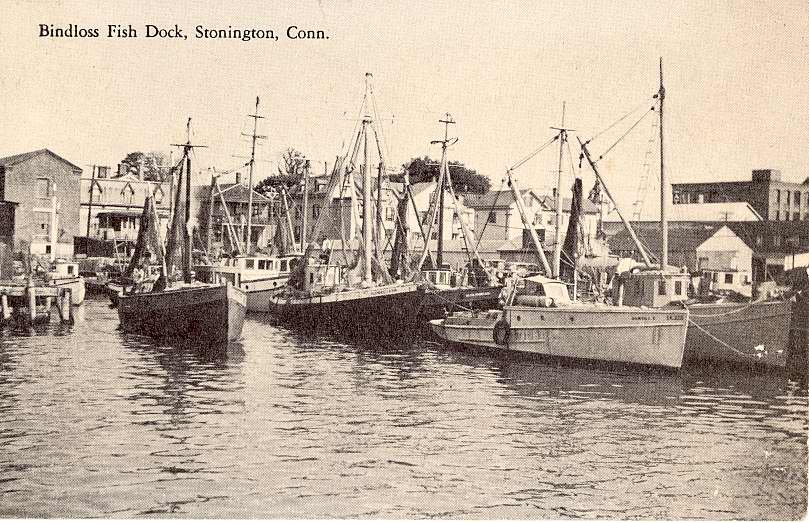

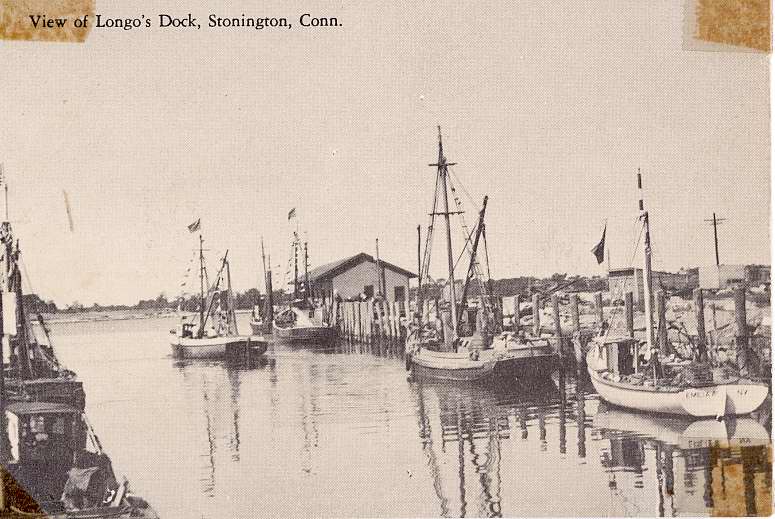

That same year Manuel, then seventeen, sailed for America with the hope that he could soon send for Connie, to join him and marry him. When he got to Stonington he moved in with his Aunt Gloria, and her husband got him a job with the Freight Steamboat Company, which operated from the Steamboat Dock, later Longo’s Dock, and now the Stonington Town Dock. He wrote to his girl,

“Connie, this beautiful America is heaven on earth compared to the old country.”

Two years later he wrote to Connie’s parents , “Glad to say that I am all paid up with my mother for my trip expenses, and I have saved enough money for Connie and I to get married. All I ask of you both is your consent to your daughter’s coming to America and to marry me.” ‘Connie’s father’s name was Joseph Bolerinho Costa. Her mother’s name was Agnes. In another letter he sent Connie thirty dollars and told her that he had some money saved up and that Aunt Gloria had two extra rooms, which they could have. Connie’s parents, however, would not agree to her coming alone, and finally decided to come with her. They sailed in March 1904, and on arrival went to Aunt Gloria’s house; but not long after, the Costas and Manuel moved to two apartments on Cross Street. Manuel and Connie were married January 1, 1905. She was then eighteen

Manuel continued to work at the Freight Steamboat Dock, and Mr. Costa got a job fishing with Fred Ostman, who owned a boat, and also a fish market. It was the only one in town. Connie’s mother took in boarders and they were all able to get along. On November 2,1906, Connie’s first child was born and christened Manuel Madeira, Jr.

The Blizzard of 1908 and a Tragedy in the Madeira Family.

Now Mary Madeira tells the story. “In early December of 1907, a very cold Sunday morning, I was running home from Sunday school, when I saw outside of our front door, Dr. Brayton’s horse and buggy. I ran up the back stairs very excited and said, “Dad, who’s sick? Where’s Ma?” “Your mother is downstairs,” he said, “Connie isn’t feeling very well, but she will be all right.”

It was two o’clock in the afternoon when mother came up and told us that Connie had given birth to another boy. On Christmas day the new baby was christened and named Joseph. Manuel and Connie’s apartment was on the first floor. Being near the water, it was very cold and damp. The room they slept in was on the north side of the house. During the winter months, she would hang newspapers on the walls and windows to absorb the moisture. The large kitchen stove burned wood during the day, and coal at night. When the weather got really cold, bricks were put in the oven during the day, and before bedtime they were wrapped in flannel and put between the covers at the foot of the beds. Manuel, Jr. slept between his mother and father, and baby Joe in his rocking cradle. In February, two months after baby Joe was born, a blizzard dumped at least two feet of snow and paralyzed our town. It started to snow early in the morning. By noon it was very cold and a gale of wind blew the snow in all directions. Manuel and Dad were preparing for the worst. They went to the market and bought extra food and kerosene. When they came back they said it was the worst storm they had ever seen. Night came, still snowing, the windows were blinded with snow. At nine o’clock in the evening, Dad set the alarm clock at 4:00 am, and went to bed. I remember so well, Connie putting a woolen cap and mittens on baby Joe and an extra blanket over him in the cradle. It was 9:45 p.m. We bade good-night, came upstairs and went to bed.

At 4:00 in the morning Dad’s alarm clock rang. I awoke, I could hear them shaking the ashes in the stove and tapping on the water pipes which were frozen. There was no water for coffee, but Dad managed to make a little with the water in the kettle. Suddenly we heard Connie screaming hysterically from downstairs. Dad ran down and Mother. I got up and ran after him. I was in a daze, thinking it was a fire, and followed them.

There was Connie with baby Joe dead in her arms. Manuel was crying with Manuel Jr. on his lap. Manuel had set the alarm at midnight to take care of the fire in the stove, Connie awoke, picked up baby Joe, changed and nursed him and then put him back in his cradle. When Connie awoke she noticed baby Joe wasn’t breathing, and was blue in the face. When she picked him up he was stiff. Mother took the baby away from Connie and laid him on the bed and said, “How on earth are we going to get a doctor with no telephone and the blizzard outside?”

“Dear God,” she said, “help us get through this ordeal.” At daybreak, Manuel got dressed in his fishing clothes and started out to the back door. The wind had drifted a bank of snow outside the doorway and he couldn’t make his way through. He came in and got two shovels. Dad and Manuel made a path to the gate. By now it had stopped snowing, but the snow had drifted and it was freezing cold. They came in and started figuring out how they were going to get water to start breakfast. They went down the cellar and made torches with kerosene and rags and in a short while we had some water, so mother started the coffee.

After breakfast Manuel and Dad went out and shoveled some more. At 7:00 am. Manuel left for the doctor. An hour later, Manuel and Dr. Brayton came in exhausted. The doctor, went to the sink to wash his hands. When he saw the faucet just dripping he turned around and said, “What happened here?” We explained, including the torches. He then went into the bedroom where the baby lay and examined him. He told us that the baby had died of exposure. He looked around and noticed the windows and walls covered with newspapers and said, “It’s a wonder you people haven’t died of pneumonia with this dampness.” Connie, heartbroken, was trying to explain in broken English what had happened during the night. The doctor patted Connie on the shoulder and said, “don’t cry, my dear, God will give you more babies, just make sure you move out of this house before the next baby comes.” The doctor signed the baby’s death certificate and said, “When I get home I’ll call the undertaker and let him take over from here. I doubt if a funeral can take place at once. Usually, I make my calls by horse and buggy but the way it looks, I’ll have to make them on foot for some time.” There was no funeral and it was some time before the baby was buried.

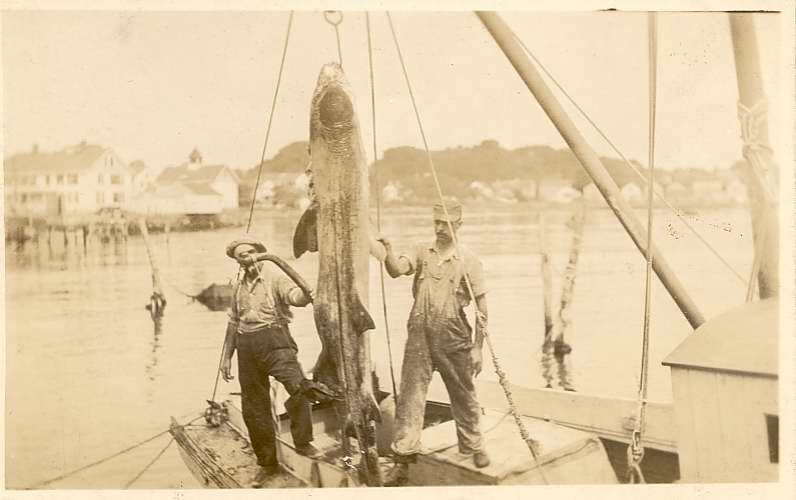

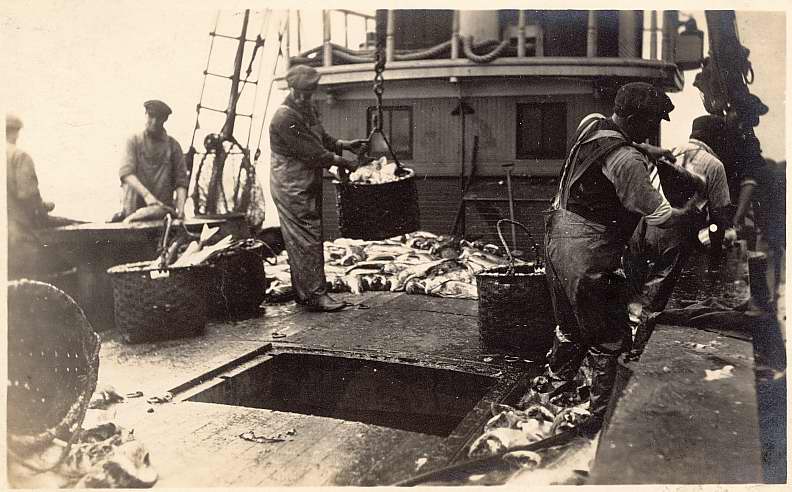

A Fisherman ‘s Life

Manuel and Dad had decided to fish together, and bought a lobster boat, and in the summer they would go out for lobsters. The winters were severe but when the weather permitted they fished with hand lines and trawls. Most of their spare time was spent building lobster pots and making twine funnels and other equipment for the pots. This sort of fishing went on for several years. I remember one cold and windy day, when Manuel and Dad were returning from fishing, they had had a rough time coming ashore. Dad came in half frozen, rubbing his ears and face. His feet were stiff and cold. Mother helped him remove his newspaper-lined boots, when suddenly I heard mother say, “Oh, my God. What has happened to your fur?” She was referring to his icicled mustache. Dad replied, “Well, you see, my southwester sprung a leak and it froze!”

In the late fall (1908) we moved to another two-apartment house on CrossStreet. Connie was pregnant again. With the winter coming, the hazards that Manuel and Dad had experienced the year before had taught them a lesson. They tried to figure out ways of better living through the hard winter months. Just before Thanksgiving they took a walk to the country, looked up a farmer, and bought a pig, and left it there to fatten up. A week before Christmas the pig was butchered. Connie and Mother made sausages with the hams; we had salt pork for baked beans and lard for homemade breads.

After Christmas, the codfish and hake were coming in. Dad and Manuel went clamming. They opened them and saved a gallon for chowder and the rest was for bait. When the catch was too small to ship, they brought the fish home, cleaned and salted them down. In a few days the fish was tied by the tails and hung up to dry in the sun. We enjoyed many dinners of codfish cakes and red beans. Farmers came around and sold potatoes very cheap, so we always had enough.

We never had any trouble storing food for the winter because the cellar was below freezing. Connie and Mother each bought a 150-lb. barrel of flour, which they kept in the pantry. Homemade bread and jams were a favorite the year round in our house. Mid-February Connie gave birth to her third son, Joseph, named for the second one that died. The ocean had frozen about 18 inches deep from the dock to the inner breakwater and to Sandy Point. The fishermen walked on the ice, broke holes with spears, and fished for eels. The kids had a grand time sliding for many weeks. The weather kept the boats tied up, and the skippers had lots of sawing and chopping.

“World War I was at its critical stage, and many good paying jobs were available for defense work. Joe got one in a nearby shipyard. In the early spring of 1918, I received a letter from the landlord, a notice to vacate. A ship-construction company had bought the entire waterfront, where we lived. A large house, containing four apartments, was to be built there. After Manuel got home from fishing, and had finished a hearty meal, Connie gave Manuel the mail which contained his fish returns and the notice to move, and said to Manuel, “Oh, dear God, where on earth are we going to find a tenement for nine people and another one on the way and convenient for fishing too?”

THE LIFE OF A

FISHERMAN’S FAMILY

“The alarm clock was set at 4 am. As always, Manuel would get up to watch the weather. I would start coffee and call the boys. When they were ready he would serve the coffee and then shortly they left. Connie had prepared the basket of lunch the night before. On busy days she would be up at 4 am. with the others. There was the bread to be baked, the boiler had to be put on the stove, the washing of clothes, and six children to get ready for school. Then of course there was the daily cooking to feed her family of thirteen. The oldest daughter Mary worked at the Velvet Mill. Mother would do the mending and patching and taking care of the fire. The hardest job of all was taking over for Connie during the confinements of childbirth and sickness.

A strong wind would often drive the ST. PETER and her crew back to shore with a poor catch. Somehow, Connie would manage to have either a clam chowder or beef stew and always the fresh, hot corn meal bread (Manuel’s favorite) waiting for them.

Three years later Connie, carrying her fifteenth child, developed a kidney ailment while in her seventh month of pregnancy. She was the first patient to ride in the first Stonington ambulance to the Lawrence Memorial Hospital in New London, Connecticut, where she gave birth, by a Caesarean section, to a premature baby girl. Connie died February 20, 1926 at the age of forty. The baby died the following day and Connie was laid to rest with her baby at her side. The following Wednesday the funeral took place during a deep blizzard. Connie’s death meant the loss of a great champion, who had fought bravely through the crises of life and death that plagued her husband and family.

Two months later Joe and I and our baby daughter moved to School Street, Stonington. Manuel searched high and low with no luck. He was well known and had good credit SO he decided to seek advice from Mr. Broughton, Real Estate Agent and

the Town Sheriff. In a short while, with the agent’s help. Manuel was able to borrow two hundred dollars as a down payment and bought a large two-tenement house, on an easy payment plan, at 9 Omega Street. Another son Lawrence was born in June, and in July they moved to their permanent home.”

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

FLU EPIDEMIC

“The influenza that broke out and killed millions of people throughout the world, struck Stonington in September1918. Young and old were stricken. The dead were taken immediately for burial to combat the spreading of infection. Joe and I came down and our baby daughter died. She was taken one hour later from us for burial. Manuel and his seven children were all sick and put to bed. Mother, Connie, and baby Lawrence did not catch it. Connie, masked, nursed the others. Dr. Taylor made morning and night calls. Manuel developed bronchial pneumonia and was treated with hot mustard and onion poultices on his chest and back, both night and day. Fortunately, with the help of God, Connie and mother fought this dreadful disease and were able to nurse the sick and keep up their daily tasks throughout the whole ordeal with no bad effects. Within the next month the children had recovered and were back in school. Manuel, after three weeks in bed, was up and around but with poor resistance which lasted for months, and was unable to return to work.”

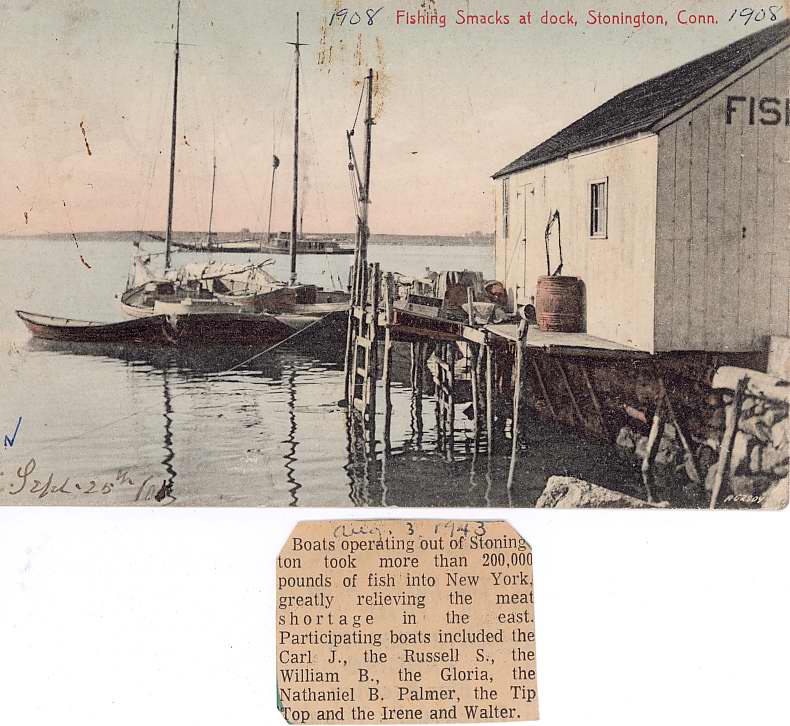

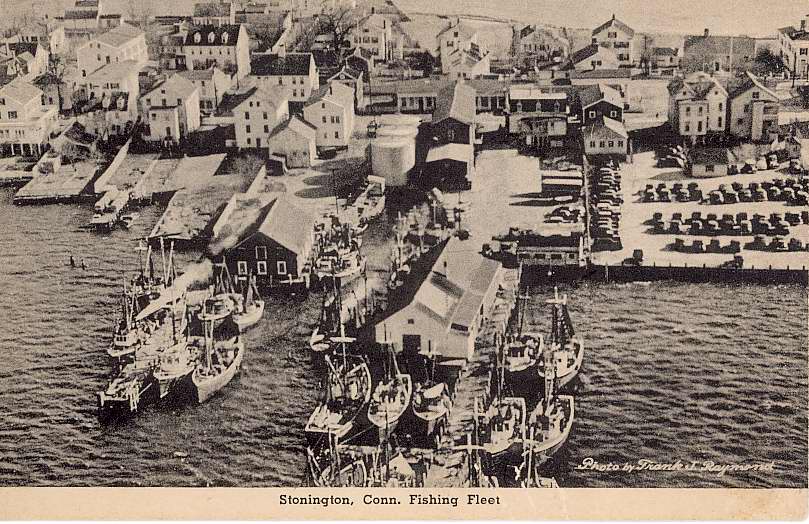

People watched from their windows, crying for their loved ones they had recently buried from the flu. In the year that followed. Manuel was much plagued by illness. He was subject to bronchial coughs and pleurisy which kept him in bed for weeks during the winter months but by mid-spring he was able to resume his lobstering. Many of the same hardships continued until Manuel’s three oldest sons were old enough to work. During the winter months the boys fished, which helped to make ends meet. Since the boat Manuel owned was rather small and the boys enjoyed fishing with their father, they decided to build a larger boat for dragging. For this was the St. Peter. She was built at the Franklin Post Yard in Mystic.

ARMISTICE DAY

“November II . 1918. The war was over. Mill and factory workers, school kids, fishermen, mothers pushing baby carriages, all took part in parading in the streets in a joyous celebration. Bands gathered and played marches. Many a guardian angel to the children she so dearly loved. In grief and sadness, mother and the two oldest daughters, Mary and Rosella, went about their daily tasks, sacrificing much to keep the family together in the belief that this would be what Connie would want most. Her dear soul was in heaven. Within the year Manuel married a widow, with a seven-year-old son named Anthony. The three oldest boys, Manuel, Jr., Joseph, and Tony went on their own and married, but remained as a crew fishing with their father. Shortly after, the daughters left, leaving the youngest, Agnes, six years old and the remaining four boys, Frank, Lawrence, John, and Alfred at home.”

MACKEREL FISHING

“With the prospect of a good mackerel season in sight, Manuel decided to buy a seine. It was seventy-five fathoms long and cost him five hundred dollars. This kind of fishing required extra work, and an extra hand was hired for setting and

hauling. Manuel hired his brother, Joe. Joe didn’t need an alarm clock with his brother’s prompt rapping on the window at 4 am, every morning to get him up. I would get up too, in order to make fresh coffee and to have his lunch ready before he left.

The men fished between Watch Hill, Block Island, and Montauk Point. The net was set at the first sight of mackerel.

They averaged a load of seventy to eighty barrels, depending on the number of hauls in a day and the capacity of ST. PETER, and would dock in the afternoon. Many times, ST. PETER and the other boats which were mackerel fishing had to wait for more barrels. The fish were sent to market by rail. One morning Joe came home unusually early and in a happy mood. Not expecting him I said, “What’s the matter, Joe, breakdown?”

“Oh, no,” he said. “We didn’t break down, but we almost sank with a load of mackerel from the first haul. We got short of barrels. While we are waiting how about fixing me something to eat?” A quick meal of fried linguica, homemade bread and bottle of beer, fixed him up and he left once again for the dock. When he came back, late that afternoon, he told me that they had shipped eighty-three barrels of mackerel which had brought a good price. Manuel and his crew of four fished for mackerel for three seasons and prospered. Then he once again returned to dragging and mending nets.

A SAD EVENT

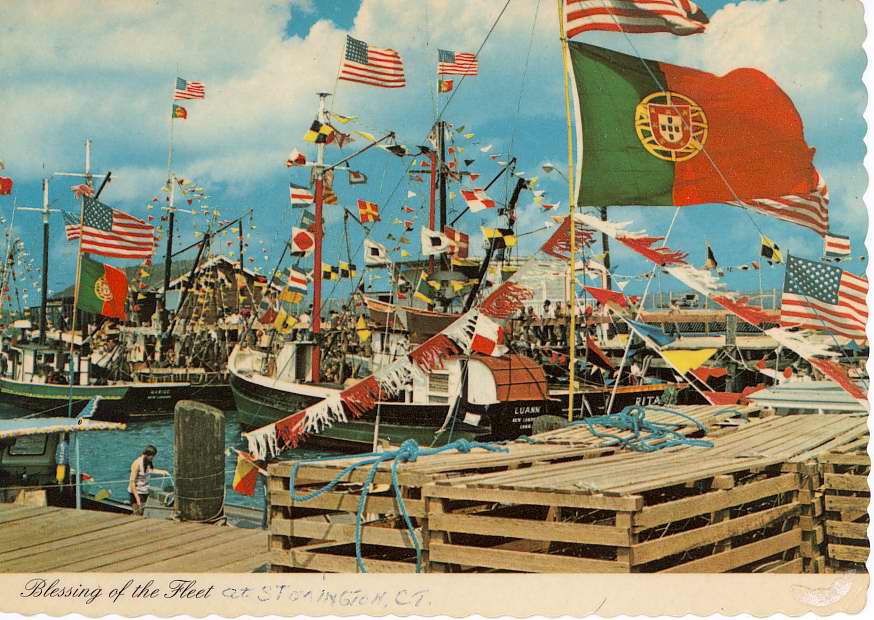

“In the early Spring of 1948 Manuel’s boat, ST. PETER, had engine trouble and was towed for repairs up the Mystic River to the Lathrop Engine Company, in Mystic. Meanwhile, Albert, now 21, and Alfred were fishing with their brother Joe on his boat, CONNIE M., until ST. PETER was ready for fishing.

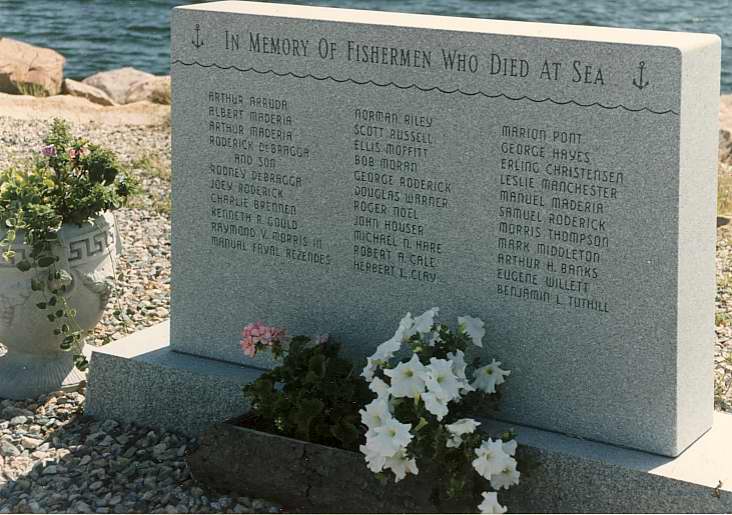

It was one week before Easter Sunday, around noon, on the choppy Block Island grounds. The men were setting the net, when one of the ropes from the net got caught on the stern bitt. Albert went to pull the rope clear, but was caught in the line and pulled overboard. Alfred put the boat in neutral when he saw his brother go over. When he sighted him he stripped off his boots and plunged into the sea, but lost sight of his brother and finally came aboard again. Albert was missing. Joe signaled the other boats that were fishing in the area, and they all took part in a search for Albert. For one week the fleet dragged and searched but Albert’s body was never recovered.

This tragedy greatly affected Manuel and his wife. Joe was so shaken from this sad experience he tied up the CONNIE M. until he was able to regain his strength and courage and the whole family was deeply saddened.”

“The remainder of this story covers the final twenty-eight years of Manuel’s life. Five children were born to Manuel and his second wife Mary; Albert (the first son), Lena and Arthur (a set of twins), Edmund who died during infancy, and Saltina. During the first five years, Manuel and his sons had tough fishing, in all kinds of rough and foggy weather. When Alfred and Albert reached working age, the older brothers had boats built of their own and left their father, leaving Alfred, Albert and Frank to take over and fish with their father. Manuel, in failing health, kept working and pinched to save all he could for his old age.

The next spring, ST. PETER was back at its homeport and ready for fishing. With the warm weather in sight, Manuel with his will of iron attempted, once again, to fish with his two sons, Alfred and Frank. They fished through the summer months, up until in the late fall, but Manuel was stricken again with his bronchial ailment and was laid-up for the winter.

At last, he reached the point where he could no longer cope with fishing, and Alfred and his brother-in-law, Charlie, took over the ST. PETER.” “Manuel longed to make a trip back home to visit his elderly mother of ninety-four whom he hadn’t seen in forty-seven years, and his sister Lucy who was born after Manuel had come to America.

It was late fall of 1949. Manuel flew by Pan American to the Azores. There, he was greeted by his brother and sister, Antone and Gloria. They had already been notified and were waiting for Manuel at the Santa Maria Airport. They went by boat to Vila Franca.

On arrival, Manuel was greeted by a large group. He was embraced by his dear mother, who by that time had poor eyesight. Lucy cried with joy upon seeing her brother for the first time. A joyous reunion took place and lasted throughout Manuel’s stay.

During his stay Manuel had the pleasure of giving away his niece in matrimony. Pictures were taken of the family at the wedding. The remaining months of his life were spent in and out of bed in a serious condition. A television set amused him during the day. His family would come and bring him homemade foods. His fishermen friends visited him often and together they would reminisce about the old happy days and the good old ST. PETER. These were the times that helped to brighten Manuel’s life. A shot of brandy was always at hand to serve to his friends and together they spent many cheerful evenings. Finally he was forced to leave his home and was taken in by his daughters, Lena and Saltina, who lived together. They were very kind to their father. The doctor would make daily calls. His children were at his bedside when the end came.

He died on May 9, 1954 at the age of sixty-nine. Funeral services took place at his home on Omega Street. The large crowd at the church and cemetery proved that the memory of honest, courageous, Capt. Manuel Madeira would remain alive forever. Manuel was buried at Connie’s side in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Stonington Connecticut.

1902-1954

Manuel Madeira died on May 9, 1954 at the age of sixty-nine.

Welcome to Historic Stonington.

Our mission is to preserve, interpret, and

celebrate the history of all of Stonington.

©2023 Historic Stonington | Site Refresh by Dessa Lea Productions

P.O. Box 103, Stonington CT 06378 | director@historicstonington.org | (860) 535-8445

"*" indicates required fields

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: Historic Stonington, 40 Palmer Street, Stonington, CT 06378, US, http://www.historicstonington.org. You can unsubscribe at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

©2023 Historic Stonington | Site Refresh by Dessa Lea Productions